2 3 4 Inch Black Powder Shotgun Shells

July 01, 2019

For the first time, I believe in modern history, we're going to look at black powder shotgun shell ballistics from a real pressure gun with real science and then at their relative equivalents with modern nitro powder. While the performance is not new, the propellants are. First, we have Olde Eynsford black powder, which is the first modern powder, at least in my experience, to be equal to, or very nearly equal to, the best English powders of the late 1800s. The further mission is to find replacement loads for the now-discontinued DuPont/IMR powders that have been the foundation for low-pressure shotgun loads for more than 40 years.

In certain contexts, it can be said that rifles and handguns thrive on velocity—and high velocity at that. Shotguns defy that idea in spite of the fact that steel shot and modern mentality have generated a lot of high-velocity shotshell loads. First, a shot pellet is a ballistic shuttlecock. It sheds velocity like a thrown feather. Launching pellets fast almost always comes at the price of pattern quality, and 1,200 fps, just at or just below the speed of sound, is about as good as it gets.

Basics of Black Powder Shotshells

I began by test-firing shells loaded with Olde Eynsford powder in 16-, 12-, and 10-gauge guns. The loads fit the original 19th-century recipes, where the powder was designated in drams. Because we are delving into a world of the obscure, we might as well understand the ever-present dram. A dram, contrary to its common use as a volume measure, is really a unit of avoirdupois weight, equal to 27.5 grains, roughly 256 drams to the pound, just over a half-ounce. (By the way, the origin of a "pound" is the weight of "7,000 plump grains of wheat." And, yes, that is the "grain" we all use to measure powder today.)

This dram is still seen today on shotgun shells as a sort of archaic way of defining velocity and performance, with perhaps the most common shell being called out by "3 drams 1 ounce." My test loads were 2¾ and 3 drams in the 16 gauge; 3, 3½, and 3¾ drams in the 12 gauge; and 4¼ drams in the 10 gauge. As you look at the tables, you will see that the velocities are not coincidentally hovering around 1,200 fps.

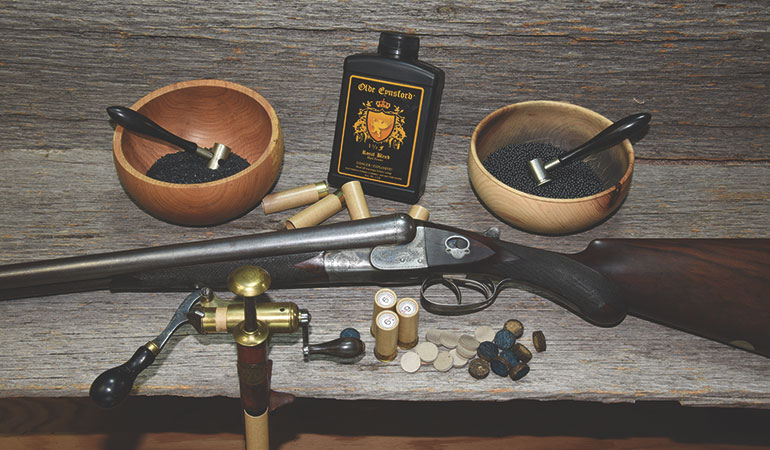

Black powder shells need a different sort of wadding than the plastic wads we have come to know and love. Black powder has a serious disagreement with plastic wads. We could blame this on ancient spirits, but more scientifically, the gritty nature of black powder fouling scrubs off some plastic and creates troublesome fouling. Also, black powder shotshells require lubricant, just like rifle or handgun ammunition, but instead of introducing the lube with the bullet, here we include it with the wads. A black powder shell uses some sort of hard card over the powder and then a flexible "fiber" wad under the shot. This fiber wad, made of various vegetable materials or felt, should be soaked with a good black powder lubricant. Ox Yoke Wonder Lube is perfect, as is SPG bullet lube or several of the other non-petroleum black powder lubes.

You can buy pre-lubricated fiber wads under the Ox Yoke name or apply your own lube to wads by warming the lube and wads in a plastic bag in a microwave oven. I like to use a thin card wad on top of that lubricated fiber to keep any shot pellets from sticking to the wad. Also, black powder shells need to be roll-crimped instead of the now-common "star" crimp. This is simply a "space-saving" gesture. Black powder takes up significantly more room in the shell than its modern nitro counterpart, and the roll crimp requires much less of the shell's length than a star crimp and leaves room for the all-important wads.

In addition, in the land of black powder is the ingrained fear of the barrel-rotting stigma and horrid cleaning process necessary to eliminate the black powder residue. To begin, it's really helpful if we dispense with witchcraft and "known truths" about black powder. First, your gun's barrels will not begin to rot the second you squeeze the trigger—or even by the next morning. The demon of the past was not the black powder itself but the corrosive primer, and it was the corrosive salt in that primer's residue that did indeed create rust very quickly. Black powder on its own is pretty benign. It will attract moisture, so cleaning your barrels is a good idea, but also so it is with nitro.

Now the real shocker: It is easier and quicker to clean barrels fired with black powder than with nitro powder. The optimal solvent for the job is one part Ballistol and four parts water. I put my patch or paper towel on an undersized bore brush, dampen the patch with the mixture, and push it through the barrel. I take this first patch off at the muzzle. Then with a second wet patch, I make two or three passes back and forth and follow that with a dry patch. After the dry patch, I apply either straight Ballistol or Wonder Lube with a final patch.

But beyond all of that, why would anyone want to use black powder shells? The most obvious reason is nostalgia. Good old guns deserve the original powder. But then there is the surprising concept that black powder shells can actually offer better patterns than modern plastic and nitro. I have used black powder shells for a very long time, but it has been only during the last decade that I have learned their true value and have come to use them more than nitro.

There is an attendant wonder about black powder: that ancient plume of smoke. Without a good wind or a fast-crossing bird, you have no idea of the result of your shot until the bird either flies out through the side or tumbles out of the bottom of the cloud. That momentary mystery does not detract from the wonder of it all.

Nitro Substitute

Black powder is not for everyone, not even for a small minority (and almost certainly not for semiautos), but its modern counterpart certainly can be. The old SR 7625 powder was the standby powder for low-pressure loads for decades. Along with SR 4756, it did everything we asked, except perhaps burn cleanly.

Suddenly, they were both gone from the shelves, discontinued for a variety of reasons. Their ability to drive a normal shot weight, at standard velocity, at relatively very low pressure, became very difficult to duplicate.

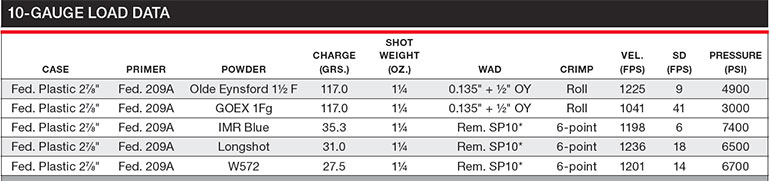

A short while later, Hodgdon began releasing new shotgun propellants. Several had very similar burning rates to the old powders, and I asked Hodgdon if they could recreate the performance of old. The criteria were simple: 1,200 fps velocity with pressure under 7,000 psi. While this pressure is somewhat higher than the norm for black powder, it is still miles below the standard 10,000-plus psi for most modern shells here in the United States. The 7,000-psi pressure level is mild enough to not overly stress the actions on fine old doubles.

It began as I issued a simple challenge to Callahan Mciver, the brilliant young ballistician at Hodgdon who did the work: "All you have to do is duplicate the performance of 1,000-year-old Chinese technology." As it turns out, it can almost be done, and he gave me a long list of wonderful loads in all of the gauges. I chose, deliberately, paper cases where possible, which meant only in the 12 gauge. Ten-gauge paper does not exist, and paper shells for the 16 gauge are rare and difficult. The loads were done with modern plastic wads, and then for a few loads, I exchanged card and fiber wads for plastic to offer that option.

While wingshooting success with black powder might be obscure, the performance of the low-pressure nitro shells is beyond question. I cannot count the pheasants I have caught with 1¼ ounces of #5 in the 10 gauges. Doves in very significant numbers, over 50 years, have almost all fallen to light 12-gauge loads. My 16s have brought home many ducks, pheasants, snipe, and more than a few geese. And at this game, I am just a piker. There are others with lifetimes of success and enjoyment, without high pressure.

In conclusion, I have not attempted to reinvent shotgun shells but simply to remind us of our history and heritage. Black powder shells are not for everyone, but if you happen to like light recoil, deadly performance, or classic guns, here is the recipe.

My personal thanks go to the Hodgdon Powder Co. and, more specifically, to the Hodgdon family, for not allowing it to be absorbed by an uncaring corporate monster. Then to Ron Reiber and his staff of ballisticians who create all of this wonderful data and design new powders for us to enjoy.

To view the 12-Gauge Load Data Chart, click here.

To view the 16-Gauge Load Data Chart, click here.

2 3 4 Inch Black Powder Shotgun Shells

Source: https://www.shootingtimes.com/editorial/blackpowder-shotshell-loading/361504

0 Response to "2 3 4 Inch Black Powder Shotgun Shells"

Post a Comment